Reimagining Climate Diplomacy: How the Lines of Power and Multilateralism Are Being Redrawn

COP 30

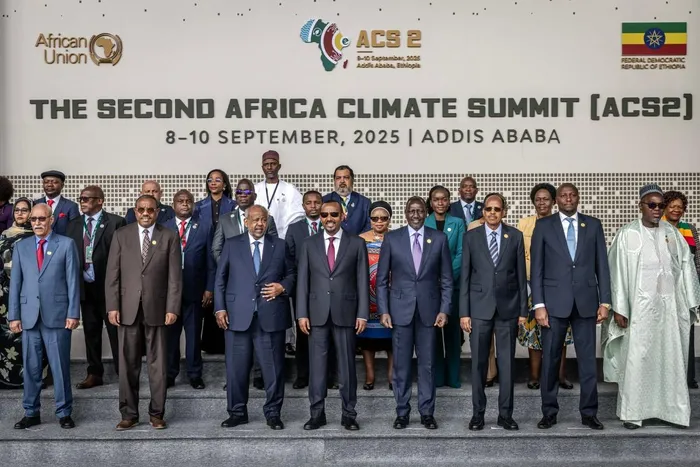

African heads of state and government representatives during the opening of the High-Level Leaders Summit at the Second Africa Climate Summit (ACS2) in Addis Ababa, on September 8, 2025.

Image: AFP

Jimena Leiva Roesch and Jonah Harris

The year 2015 was a landmark moment for multilateralism. In September, leaders from around the world adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, charting a roadmap to a just and sustainable future. And in December, world leaders once again came together to adopt the Paris Agreement, collectively committing to tackle global warming.

In 2025, the pendulum has swung to the opposite side. We are in the midst of rising nationalism and weakening multilateralism. Countries are falling dramatically short on their commitments under both the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement. Trade wars are spurring anger and mistrust among nations. The number of state-based armed conflicts has reached a new high.

But 2025 also presents opportunities for countries to recommit to the purposes and principles of the United Nations and achieve genuine breakthroughs that can benefit both the people and the planet. A relatively small number of powerful countries is driving the crisis of multilateralism, abandoning the very institutions they helped build. Developing countries can take advantage of this crisis to expand their global influence—and their global responsibility.

One area where developing countries can step up is climate action, particularly as we approach COP30 in Brazil. With the US withdrawn from the Paris Agreement and Europe distracted by the war in Ukraine, there is space for new leadership.

Climate leadership aligned with the realities of 2025 is long overdue, and climate finance is a compelling place to start. It is a well-known and oft-lamented fact that the list of countries obligated to provide international climate finance has been frozen in time since 1992, when the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was adopted.

For finance purposes, the UNFCCC divided countries into two categories: the 24 states that were members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the European Economic Community (now the European Union) were grouped under Annex II and obligated to provide climate finance, and every other country was not. In the three decades that followed, the only modification to the list was the removal of Türkiye in 2001.

For years, any hint that any non-Annex II country could provide finance was a political nonstarter. This principle, encapsulated by the language of countries’ “common but differentiated responsibilities” with respect to climate change (CBDR), remains at the core of international climate diplomacy. Article 9 of the Paris Agreement reaffirmed the requirement that developed countries provide finance without a similar requirement for developing countries.

However, it encouraged non-Annex II countries to provide voluntary contributions—a significant softening of the firewall between developed and developing countries’ financial responsibilities.

Since 1992, there have been significant economic and political shifts. A number of countries—mostly in the Persian Gulf and East Asia—now have the resources and the political ambition to become active donors. Historically, these states were strongly opposed to binding finance requirements for self-interested reasons.

Other developing countries, even the smallest and most vulnerable, also opposed any efforts that appeared to challenge the grand bargain of CBDR, even when they themselves were not being asked to pay.

Today, in a massive shift, multiple developing countries are stepping up by providing voluntary contributions or exploring innovative ways to support climate finance. Notably, COP30 host Brazil has made a $1 billion commitment to the Tropical Forests Forever Facility and partnered with the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) to launch the Amazonia for All exchange-traded fund (ETF) at COP. Brazil has also convened a “circle of finance ministers” who recently shared a roadmap to scale up climate finance.

Other countries are also voluntarily expanding their climate contributions. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) pledged $100 million to the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD) launched at COP28 in Dubai, where it also established a new $30 billion climate fund. The Republic of Korea pledged $7 million to the FRLD and has made over $600 million in pledges to the Green Climate Fund since 2014, including $300 million in 2023.

Beyond concessional finance, developing countries can demonstrate leadership through investment and by pushing for reform of the global financial architecture. Even if developing countries pursue the energy transition primarily for self-interested reasons, they still have compelling grounds for investing in the most vulnerable regions—especially Africa, which possesses 60% of the world’s best solar resources but only 1% of installed solar photovoltaic capacity.

This represents both a clear injustice and an enormous opportunity. The continent recently showcased homegrown climate solutions at the Second Africa Climate Summit and is poised to benefit as both a source and a recipient of new investment.

The logic of investing outside traditional developed economies is compelling to all seeking high returns, but it is particularly appealing to developing countries themselves, which stand to gain from shifts in the financial system. The IDB’s Reinvest+ proposal encapsulates the synergies between reform and investment, and countries around the world are showing strong interest.

Many countries in the Global South define themselves through their recent struggles for self-determination and against a global order still perceived as unfair and tilted northward. This sense of injustice gives them a sense of moral authority in the eyes of many.

That authority is a valuable resource—particularly for small island developing states (SIDS), which bear the brunt of climate impacts. SIDS used their moral authority to ensure that the Paris Agreement referenced a 1.5°C target in addition to the less ambitious 2°C goal. They have continued their advocacy with a campaign that ultimately led to a recent advisory opinion by the International Court of Justice, further solidifying the 1.5° goal.

Still, these countries that have contributed the least to climate change should not be expected to clean up the mess others have made, and their activism cannot excuse inaction by others.

Developing countries must now step up to play a larger role in global governance. Developed countries are often suspicious of attempts by developing countries to take more prominent leadership roles. Developing countries can allay these suspicions by emphasizing that, by providing more resources, they are acting as responsible global citizens and shouldering a greater share of the burden.

Thus, they also deserve a seat at the table, whether as permanent seats in the UN Security Council or increased quotas in the Bretton Woods institutions. Brazil, the African Union, and others have forcefully made this argument.

The lines of power and multilateralism are being redrawn. The unique challenges and opportunities of this moment provide openings, above all, for developing countries to assume greater leadership and responsibility in reducing emissions and transitioning to a carbon-free world. It is their moment to lead.

* Jimena Leiva Roesch is Director of Global Initiatives and Head of Peace, Climate, and Sustainable Development at the International Peace Institute. Jonah Harris is a Policy Analyst in the Peace, Climate, and Sustainable Development Program. This article was originally published at https://theglobalobservatory.org/

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.