Resolving SA's Unemployment Crisis Requires a Repurposed Economic Trajectory

YEAR IN REVIEW

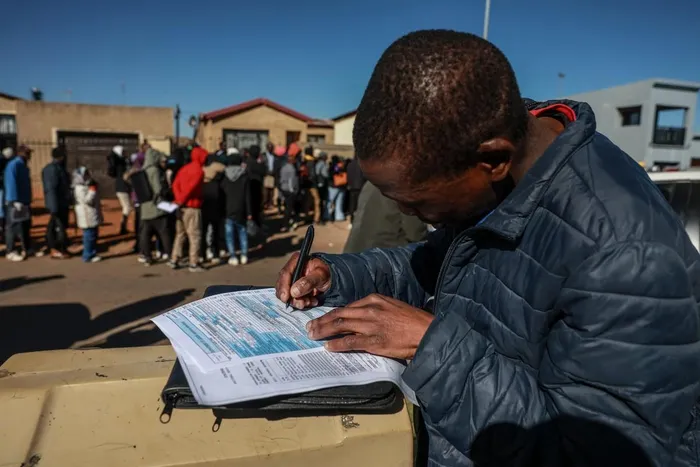

An unemployed youth fills in the Department of Unemployment and Labour work seeking registration form while queuing with others at a centre in Chiawelo, Soweto on June 27. Growth alone will not resolve the employment crisis unless its composition changes fundamentally, says the writer.

Image: AFP

Zamikhaya Maseti

As South Africa winds down 2025 and prepares to enter 2026, it does so with a guarded but undeniable sense of optimism.

The recently published Labour Market Dynamics data indicate that the economy created 248,000 jobs in the third quarter of 2025. After years of stagnation and policy drift, this outcome suggests that under conditions of stabilising electricity supply, easing logistics constraints, and modest economic recovery, the labour market retains a residual capacity to respond.

Most certainly, the economy is on a positive trajectory. The numbers matter. They signal movement where there has long been paralysis. Yet, accordingly, they must be read soberly, not as evidence of arrival, but as an opening through which the deeper structural condition of the economy must now be confronted.

The improvement recorded in 2025 was real and should not be dismissed. The stabilisation of the electricity supply removed one of the most binding constraints on production. Logistics reform began, albeit unevenly, to loosen choke points in ports and rail that had strangled growth for over a decade.

Manufacturing showed tentative signs of recovery, and mining displayed resilience amid global uncertainty. Public investment improved incrementally, while private capital edged back into the economy as policy certainty strengthened. Indeed, these developments created the conditions for employment growth, and the additional 248,000 jobs confirm that the economy is not structurally frozen.

Perspective, however, remains indispensable. South Africa’s employment crisis is not defined by quarterly movements but by scale, duration, and structure. The economy must create between seven hundred thousand and one million net new jobs every year for at least a decade if it is to absorb new labour market entrants, reduce the vast pool of unemployed people, and reverse the steady expansion of long-term inactivity.

Anything less merely manages decline. Accordingly, when measured against this requirement, the recent job gains, welcome as they are, remain modest. They indicate traction, not transformation.

This distinction matters because South Africa has, over time, repeatedly confused episodic improvement with structural change. The Labour Market Dynamics evidence shows that even during periods of growth, too many unemployed people do not transition into work. Adversely, they fall instead into inactivity, discouraged by repeated rejection and excluded by an economy that offers few credible pathways into productive life.

Youth unemployment remains extreme and volatile, defined by churn between short-term jobs, prolonged unemployment, and withdrawal from the labour force. Women continue to be concentrated in undervalued and insecure forms of work and remain disproportionately represented among the inactive due to care burdens and systemic exclusion. Racial and provincial inequalities remain etched into every labour market indicator, reproducing historical disadvantage in contemporary form.

Critically, educational attainment is no longer a guarantee of employment. South Africa is witnessing a growing and deeply unsettling phenomenon of unemployed graduates and matriculants. Most certainly, the promise that education alone would unlock opportunity is fraying. This reality exposes a profound skills mismatch between what the education and training system produces and what the economy demands. Too many qualifications remain abstract, poorly aligned, and disconnected from production.

Simultaneously, shortages persist in technical trades, engineering, digital capability, logistics, artisan skills, and applied sciences. Accordingly, a perverse duality has emerged in which educated young people are locked out of work while firms struggle to find the skills they require. This is not merely an educational failure. It is a systemic coordination failure between the State, industry, and training institutions, and it now stands as one of the most dangerous fault lines in the political economy.

The danger, therefore, lies not in acknowledging progress but in overstating its meaning. A single quarter of employment growth does not undo decades of exclusion. It does not signal that the growth model itself has shifted. Necessarily, the state of the economy cannot be assessed solely by whether jobs were added, but by whether the underlying structure of growth is changing in a way that allows inclusion at scale.

The outlook for 2026 is cautiously positive but sharply constrained. Growth is expected to improve modestly as the gains from energy stabilisation and logistics reform begin to filter through the economy. Renewable energy investment, agriculture, tourism, advanced manufacturing, and digitally enabled services are likely to perform better.

Yet, even under optimistic assumptions, growth is unlikely to exceed two percent. This remains far below the three to five percent sustained growth required to decisively reduce unemployment. Accordingly, the gap between where the economy is and where it must be defines the national dilemma.

The implication is unavoidable. Growth alone will not resolve the employment crisis unless its composition changes fundamentally. South Africa’s economy remains too capital-intensive, too concentrated, and too biased toward high skill enclaves to absorb labour at the scale required.

A new perspective on the state of the economy, therefore, demands a decisive shift away from treating employment as a secondary outcome and toward making it the organising principle of economic strategy.

The growth drivers capable of delivering this shift are neither speculative nor novel. They are rooted in the material structure of the economy and the country’s comparative advantages. Agriculture must be approached as a complete economic system rather than a narrow primary activity.

From primary production to secondary agro processing and tertiary logistics, storage, marketing, and export services, the entire agricultural value chain must be expanded and integrated. This is where employment can be generated rapidly and at scale, particularly in rural areas that have long been marginalised. It is here that food security, spatial inclusion, and labour absorption can converge into a single developmental strategy.

Manufacturing must, accordingly, be repositioned as a central pillar of economic reconstruction. This requires moving beyond enclaves and rebuilding industrial ecosystems across automotive value chains, food processing, textiles and clothing, pharmaceuticals, and green industrial inputs.

Manufacturing remains one of the few sectors capable of anchoring large numbers of jobs while supporting skills development, supplier industries, and technological upgrading. Without a decisive manufacturing revival, the economy will continue to hollow out its productive base.

Road construction and broader infrastructure development must be treated not merely as long-term productivity investments but as immediate employment engines. The rehabilitation and expansion of road networks, particularly in townships, rural areas, and transport corridors, can absorb large numbers of low and semi-skilled workers while simultaneously lowering the cost of doing business and improving market access.

Infrastructure spending, if properly sequenced and executed, offers one of the fastest routes to large-scale job creation while laying the foundation for future growth.

South Africa stands, indeed, at an inflection point. The stabilisation achieved in 2025 has opened a narrow but meaningful window. Whether the modest expansion anticipated in 2026 becomes a bridge to a repurposed economic development trajectory or collapses into another cycle of managed decline will depend on whether these growth frontiers are pursued with urgency, scale, and coherence.

The encouragement offered by recent job gains is real, but it will only endure if it is converted into a deliberate programme that systematically expands agriculture across its full value chain, rebuilds manufacturing capacity, and deploys infrastructure investment, particularly road construction, as a central instrument of employment creation.

The measure of success in the coming decade will not be quarterly job numbers or marginal improvements in growth. It will be whether the economy consistently creates work at the scale required to restore dignity, inclusion, and economic citizenship. South Africa does not lack insight into its crisis. Adversely, it has too often lacked the resolve to reorganise growth around employment.

The choice now is stark. It is whether the country commits to a repurposed economic development trajectory that places labour-absorbing growth at its centre, or whether it allows recent encouragement to dissipate into another cycle of managed stagnation. What follows will determine whether this moment inaugurates a decisive shift in the political economy or becomes yet another entry in the long ledger of deferred transformation.

* Zamikhaya Maseti is a political economy analyst and holds a Magister Philosophae in South African Politics and Political Economy from the erstwhile University of Port Elizabeth, now Nelson Mandela University.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.