Marikana Massacre Hovers over ANC's January 8 Celebration

2026 IN FOCUS

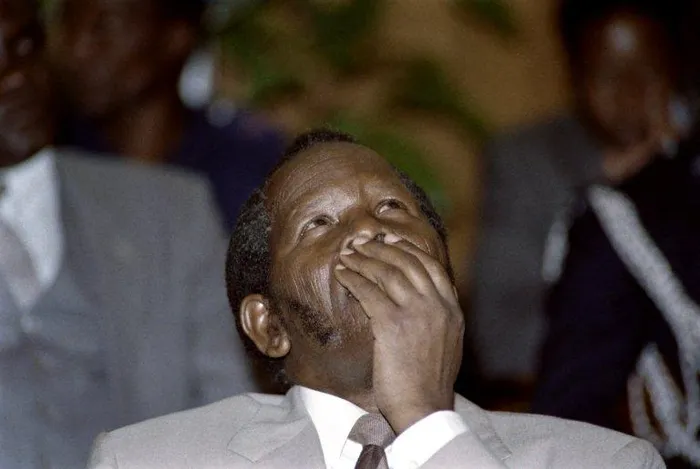

ANC president Oliver Tambo in deep reflection at the 75th anniversary of the African National Congress held on January 8, 1987 in Lusaka, Zambia. January 8th must be understood not as a ritual of nostalgia, but as a moment of reckoning, a disciplined pause demanding introspection and strategic clarity, says the writer.

Image: AFP

Zamikhaya Maseti

The African National Congress convenes its 114th anniversary on 8 January 2026 in the Bojanala District of the North West Province, a terrain upon which the deepest contradictions of South Africa’s democratic order have been etched with unforgiving clarity.

Founded in 1912, the ANC remains Africa’s oldest liberation movement in continuous existence. Longevity, however, is not a virtue in itself. History is indifferent to age. It is attentive only to purpose, conduct, and consequence. January 8th must therefore be understood not as a ritual of nostalgia, but as a moment of reckoning, a disciplined pause demanding introspection and strategic clarity.

The choice of Bojanala is neither accidental nor politically neutral. It is a choice laden with material meaning. The Bojanala Platinum District Municipality constitutes the economic heart of the North West Province, contributing just over half of the province's Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Anchored by Rustenburg and structurally dominated by the platinum group metals mining complex, the district occupies a central position in South Africa’s extractive economy.

Accordingly, to gather in Bojanala is to gather at the nerve centre of mineral accumulation, labour exploitation, and State mediation. The wealth extracted from Bojanala’s soil has long sustained corporate balance sheets, export earnings, and sections of the national fiscus. Platinum, like gold before it, has been woven into South Africa’s accumulation regime as both lifeblood and curse. Accumulation, however, is never merely technical. It is social, political, and coercive.

Consequently, Bojanala represents a spatial concentration of contradiction: immense mineral wealth coexisting with worker precarity, informal settlements, environmental degradation, and chronic municipal distress. The district thus embodies the unresolved tension of the National Democratic Revolution: political power secured, yet economic relations largely intact.

This contradiction is structural. The post-Apartheid State inherited an extractive economy organised around cheap labour, migrant systems, and spatial dispossession. While political rights were universalised, the economic base reproducing inequality remained substantially unaltered. Bojanala must therefore be read as a microcosm of the national dilemma: a democratic State presiding over an economy whose logic was forged under colonialism and apartheid and whose reproduction continues to generate social fracture.

It is therefore not incidental that Marikana is located within the Bojanala District, specifically under the Rustenburg Local Municipality. The massacre did not occur at the margins of the provincial economy. It occurred at its very core, at the precise intersection where capital accumulation, labour resistance, and State authority collide.

The Marikana Massacre of August 2012 stands as one of the darkest moments in South Africa’s democratic history. Thirty-four mineworkers were killed by agents of the democratic State while demanding a living wage of R12 500. These workers were neither criminals nor insurgents. They were participants in a struggle as old as capitalism itself: the struggle between labour and capital over wages, dignity, and the conditions of social reproduction.

Their demand was not radical excess, but an insistence on survival within an economy that systematically extracts value while externalising human cost. The attempt to recast Marikana as a “tragedy” rather than name it as a massacre was not a semantic lapse.

It was a political manoeuvre. Language was mobilised to dilute responsibility, to normalise State violence, and to insulate power from moral and historical accountability. Legal abstractions were deployed, plunging the country into a sterile linguistic dance that distanced the State from the blood on the koppie. Grammar, in this moment, became a tool of governance.

History resists such erasure. The South African mining economy has always relied on force, whether naked or institutionalised. During the 1922 Rand Revolt, more than 200 people were killed when the State intervened decisively to protect accumulation under threat. That episode revealed an enduring truth: when the circuits of capital are disrupted, coercive power is summoned. The difference between 1922 and 2012 lies not in the logic of violence, but in the character of the State that deploys it.

This is the burden the ANC must confront honestly. Marikana exposed the limits of political liberation divorced from economic transformation. It revealed a post apartheid State deeply entangled with capital, structurally dependent on mineral rents, and uncertain in its class orientation.

When confronted by organised working-class resistance operating outside institutionalised bargaining frameworks, the State responded not with mediation but with repression. This response was not anomalous. It was the outcome of unresolved structural contradictions.

The implications of Marikana extend beyond the platinum belt. The violence did not end on that August afternoon. It continues in the lives of widows and fatherless children, bearing the deferred costs of an economy that extracts value in one place while depositing misery elsewhere.

Geography, in this sense, becomes destiny. The spatial separation between Bojanala’s mineral wealth and the sites of social reproduction that sustain mining labour is not incidental. It is constitutive of South Africa’s political economy.

Migrant labour did not disappear with democracy. It merely assumed new forms, continuing to externalise the social costs of accumulation beyond the zones of extraction. Any serious reflection on Marikana must therefore extend beyond the site of violence itself to the broader social geography that made it possible and continues to sustain its afterlives.

The 2026 January 8th Statement and Rally, therefore, unfolded within the unmistakable context of the approaching National Local Government Elections. These elections loom large, not as a procedural inevitability, but as a political test of organisational coherence. They demand clarity of purpose, firmness of execution, and a sober appreciation of the material conditions confronting communities.

Accordingly, the ANC is compelled to map out a combative and grounded electoral strategy, one capable of reconnecting the movement to the lived realities of the masses. Such a strategy cannot subsist on proclamation. It must be borne by disciplined ground forces, equipped with the capacity to articulate it persuasively to the people, ward by ward and street by street.

It must speak directly to collapsing road infrastructure, the systematic neglect of State assets, including public facilities such as stadiums, and the visible decay that steadily erodes confidence in democratic governance. Consequently, cadres deployed at the coalface of service delivery must possess not only technical competence, but also the political wherewithal and moral courage to act decisively, without evasion, hesitation, or retreat.

The 2026 January 8th Statement, therefore, must present the African National Congress with an opportunity to arrest and reverse the downward electoral trajectory anticipated by polling agencies and political analysts, not through assertion, but through demonstrable organisational resolve and material responsiveness to the lived conditions of the people.

* Zamikhaya Maseti is a political economy analyst and holds a Magister Philosophae (M.Phil.) in South African Politics and Political Economy from the erstwhile University of Port Elizabeth, now Nelson Mandela University.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.