The Path to NPA Reform: Ensuring Independence and Public Trust

CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM

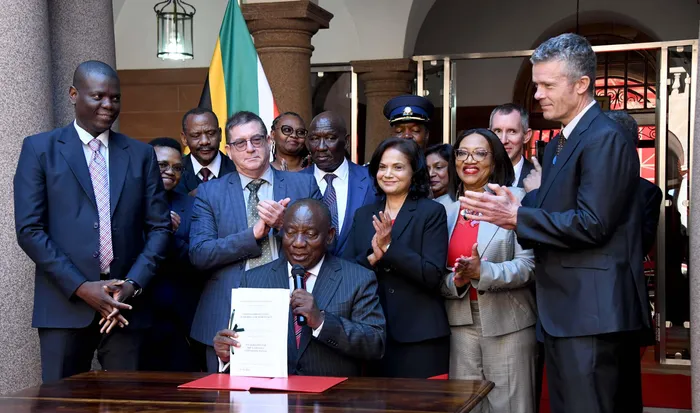

President Cyril Ramaphosa signed into law the National Prosecuting Authority Amendment Bill at the Union Buildings in Pretoria on May 24, 2024. Restoring the NPA’s independence, coherence, and public confidence will require sustained, demonstrable prosecutorial reform rather than procedural legitimacy alone, says the writer.

Image: GCIS

Dr Reneva Fourie

On 6 January, the President exercised his right in terms of the Constitution and the National Prosecuting Authority Act to appoint Advocate Jan Lekgoa Mothibi, commonly known as Andy Mothibi, as National Director of Public Prosecutions after the formal interview process failed to deliver a suitable candidate.

The Constitution places an obligation on the President to ensure that the National Prosecuting Authority is properly led and able to fulfil its mandate without fear, favour, or prejudice. The National Prosecuting Authority Act reinforces this responsibility by empowering the President to intervene when the effective functioning of the prosecutorial authority is at risk.

While the decision was legally permissible, it also reflects the limitations of a process that was unable to produce a clear and defensible outcome for such a critical position. Job interviews are not always a reliable reflection of capability. They remain an artificial scenario, the outcome of which is often dominated by an individual’s capacity for self-promotion rather than by evidence of sustained performance in complex institutional environments.

Research in organisational behaviour indicates that interviews frequently reward confidence, articulation, and strategic presentation over depth of experience and leadership under pressure. In the South African context, this limitation is further entrenched by cultural norms that discourage overt self-promotion.

Self-promotion is frowned upon in most South African cultures, and so that is an inherent subconscious block that inhibits the performance of interview participants, particularly in public and adversarial settings.It is partly for this reason that the selection process for most senior positions in South Africa’s public service is ordinarily supplemented by competency-based assessments.

These assessments seek to evaluate ethical reasoning, judgment, leadership, and strategic capacity through structured methodologies rather than performative interaction. Their absence or marginal role in appointments of this nature raises questions about whether interview performance is being overvalued at the expense of demonstrated institutional competence.

These concerns are amplified by the unique nature of the interview process for South Africa’s National Director of Public Prosecutions. Interviews for this position take place publicly, requiring candidates to manage not only the expectations of the panellists but also the scrutiny and often hostile commentary of members of the public who freely express uninformed opinions on social media. This environment places a premium on media management and emotional composure, attributes that may not align neatly with the practical demands of leading a national prosecutorial authority.

The extent to which such a process can accurately identify the most suitable candidate remains open to debate. These factors provide important context for the outcome reached by the advisory panel established by President Ramaphosa. The panel concluded that none of the shortlisted candidates were suitable for appointment based on the interview process.

While this finding must be respected, it also reflects the inherent constraints of the methodology applied. The conclusion does not necessarily imply an absence of capable candidates in the pool, but rather highlights the difficulty of assessing prosecutorial leadership through a public interview format alone. While appreciating the sterling track record of Advocate Andy Jan Lekgoa Mothibi, it would be inappropriate to assume that he would perform better than candidates who were deemed unsuitable through the formal process.

Advocate Mothibi’s professional background is nonetheless central to understanding the rationale behind the appointment. As head of the Special Investigating Unit, he has led an institution mandated to investigate serious maladministration, corruption, and unlawful conduct within state institutions. The Special Investigating Unit operates through presidential proclamations and relies heavily on civil litigation to recover losses suffered by the state.

Undoubtedly, the Special Investigating Unit has a sterling track record in recovering public monies and assets attained through corruption, maladministration, and malpractice. Its annual reports reflect substantial recoveries and successful court outcomes. The success of the Special Investigating Unit can, to a large extent, be attributed to the systems it has developed to manage consultants and external expertise in a structured and accountable manner. These systems enable the unit to mobilise specialised skills while maintaining central oversight.

This model has proven effective within the specific mandate of the unit. Its relevance to the leadership of a prosecutorial authority, however, is less straightforward. Running an efficient public prosecutorial service cannot be outsourced. The constitutional mandate of the National Prosecuting Authority requires direct leadership, internal coherence, and firm control over prosecutorial discretion. Charging decisions, case prioritisation, and prosecutorial conduct must be managed within a tightly governed institutional framework.

This requirement is particularly significant given the persistent allegations of political and even criminal influence over elements of the prosecution process. These allegations point to systemic weaknesses that cannot be resolved through administrative efficiency alone but require sustained institutional reform and assertive leadership.

The responsibilities of the NDPP extend beyond managerial oversight. The role includes setting prosecutorial policy, ensuring consistency across the organisation, and protecting the independence of prosecutors. It also involves oversight of specialised units, engagement with law enforcement agencies, and accountability to Parliament.

Whether experience in a civil recovery and investigative environment sufficiently equips an incumbent to address these prosecutorial challenges remains an open and consequential question.

Time will determine whether this appointment will bring stability to the National Prosecuting Authority, restore public confidence, and meaningfully strengthen the criminal justice system.

The NPA has endured prolonged instability, reputational damage, and declining trust. Reversing this trajectory will require more than continuity in leadership. It will demand demonstrable improvements in decision-making, institutional discipline, and prosecutorial outcomes.

Ultimately, the President acted within his constitutional and statutory powers, but the process that preceded the appointment exposes deeper flaws in how prosecutorial leadership is assessed. Public interviews alone are ill-suited to measure institutional competence, ethical judgment, and leadership under pressure.

While Advocate Mothibi brings a credible record in investigation and recovery, the true test lies ahead. Restoring the NPA’s independence, coherence, and public confidence will require sustained, demonstrable prosecutorial reform rather than procedural legitimacy alone.

* Dr Reneva Fourie is a policy analyst specialising in governance, development, and security.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media, or The African.